Specimen Spotlight

We have over 500,000 specimens. While much of their utility comes from looking at many specimens together to identify biodiversity patterns, each individual specimen also has value. Every single object in the collection has a unique story to tell. Here are some of those stories.

A vine from another time: specimens tell us the origins of weeds

By Nicholas Bhandari

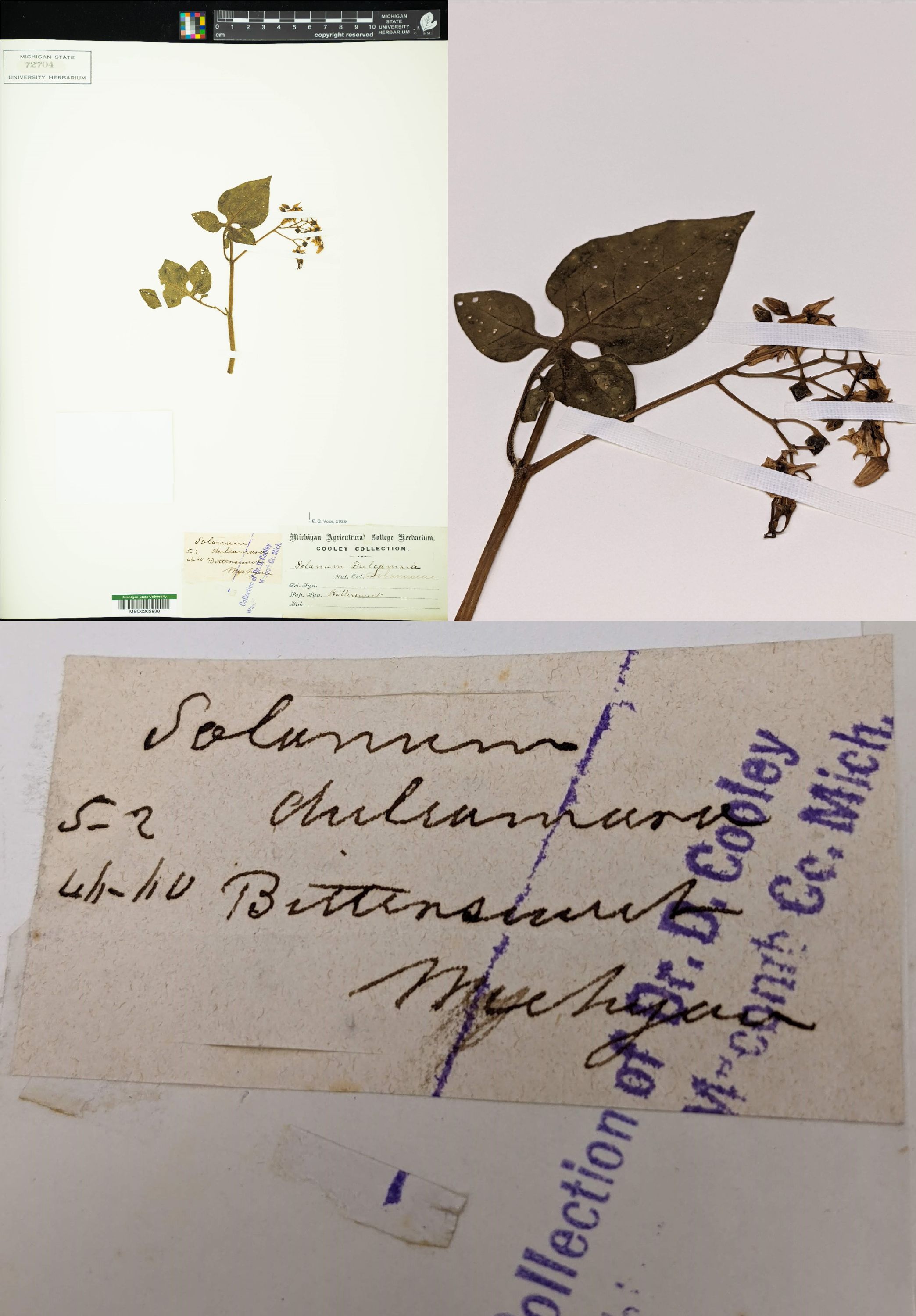

The MSU Herbarium has its roots in a generous donation of Dr. Dennis Cooley’s personal collection in the years after he passed in 1860. His earliest specimens date to around 1815. One of them was an undated individual of Solanum dulcamara, called bittersweet nightshade. Bittersweet nightshade is a naturalized nonnative vine in the Great Lakes region, introduced from the Old World. We don’t have any specimens of S. dulcamara at the herbarium collected before Cooley's time. Because this was in the herbarium’s earliest collection, it may be that this particular individual was the first documented occurrence of this nightshade in Michigan, found by Dr. Cooley in Washtenaw County.

Bittersweet nightshade (Solanum dulcamara) specimen collected by Dr. Dennis Cooley in Michigan. Image credit: Matt Chansler

Fake flesh: one weird plant's quest to achieve pollination

By Heidi Slawson

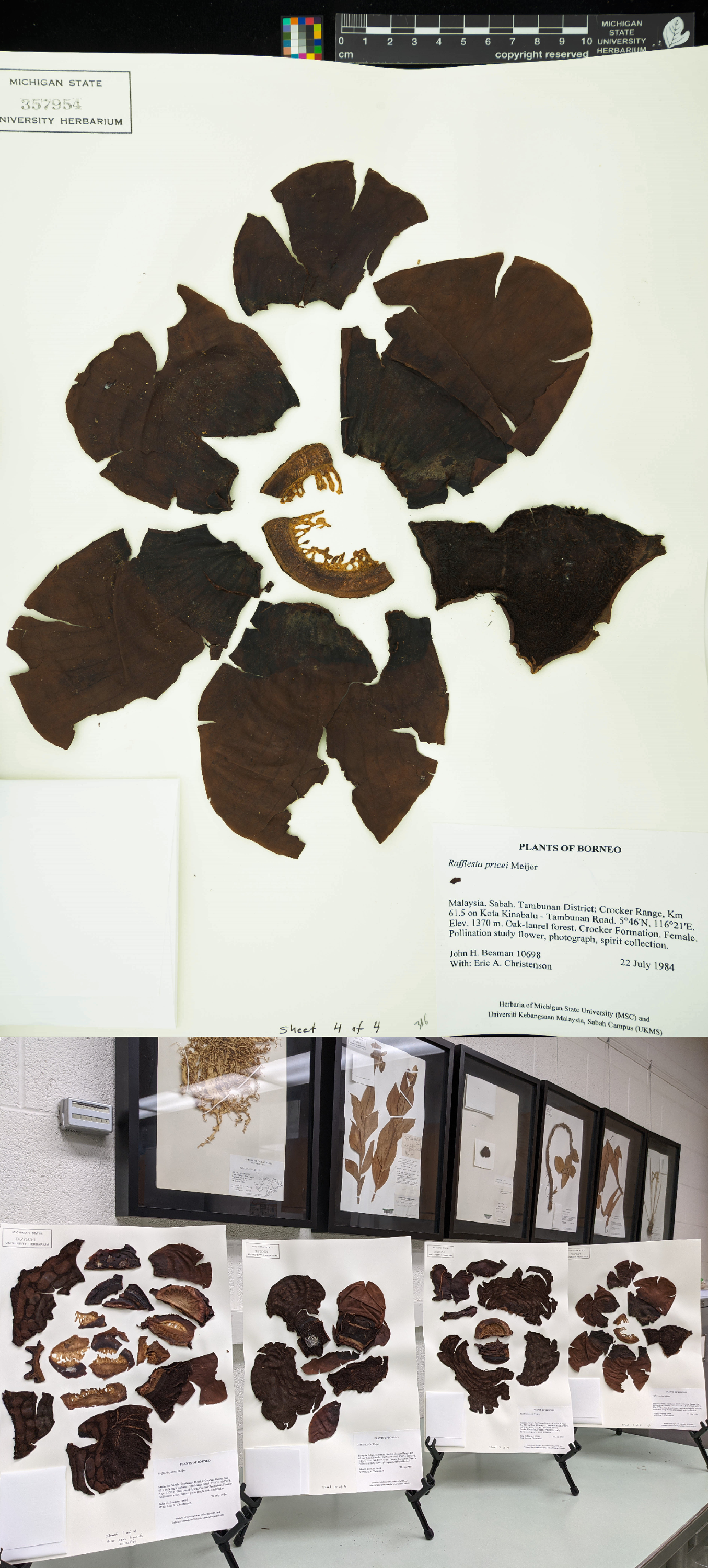

This specimen is a voucher specimen for a groundbreaking pollination study of Rafflesia. Rafflesia is a threatened genus of plants with the largest flowers plants known, with some being up to a meter across. Native to the rainforests of Southeast Asia, these parasitic plants do not have their own roots or stems but grow as threads inside host vines in the genus Tetrastigma. They are nicknamed ‘corpse flowers’ because of the stench they give off, similar to that of rotting meat. This process was discovered and recorded by former MSU Herbarium Director, Dr. John Beaman and his colleagues.

Rafflesia pricei produces enormous flowers that must be sectioned across multiple sheets. Image credit: Matt Chansler

A very knotty weed: recording fallopia in ingham county, Mi

By Taylor MacKenzie

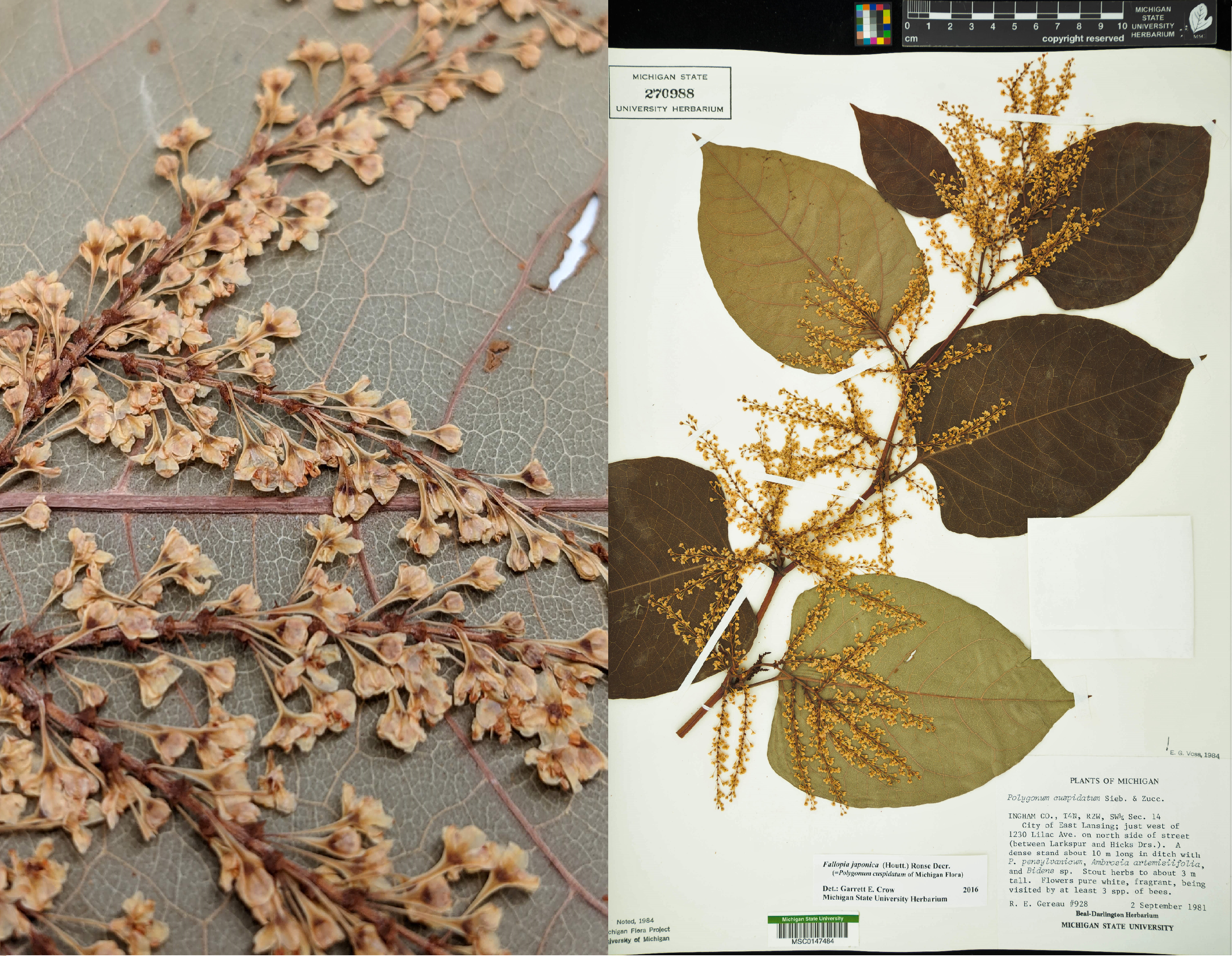

The MSU Herbarium houses a specimen of Fallopia japonica, Japanese knotweed, that was used for establishing a record of the species in Ingham County. This is a shrub native to Japan and other parts of East Asia that is classified as an invasive species by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. Fallopia japonica poses a unique threat to humans because it can grow through many building materials, including concrete.

Left: Japanese knotweed flowers. Right: specimen. Image credit: Matt Chansler

Precious stone or crusty rock? how a lichen species is born

By Anna-Katherine Fournier

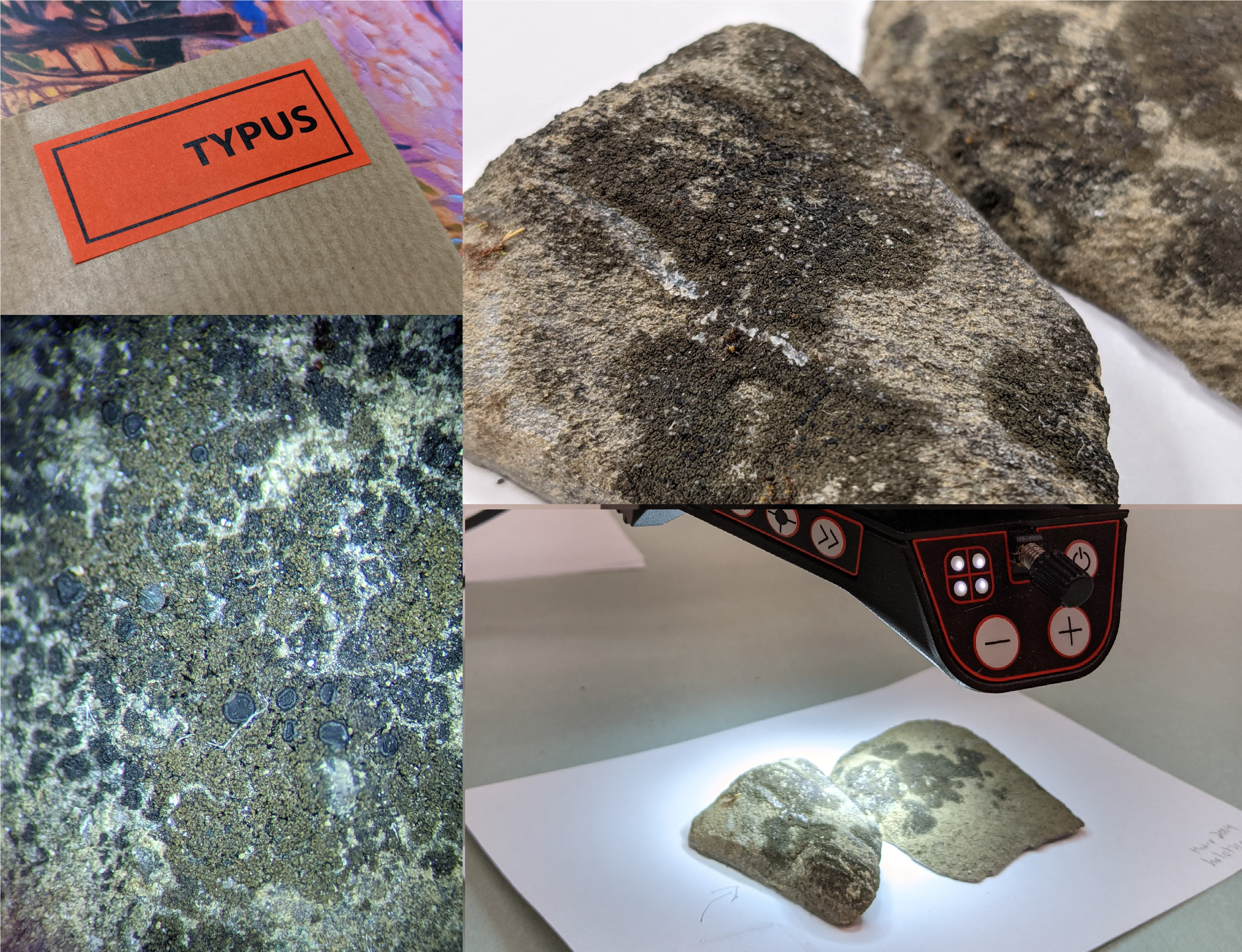

This lichen specimen is the original specimen that was used to describe a new species (a "type" specimen). For a new species to be recognized there must be an herbarium specimen that the publication can refer to. Placynthium glaciale was first found in 2014 in Glacier Bay National Park. It is a tiny brown lichen, spanning only 0.2 mm thick and 3.5 cm in diameter. Lichens are composite organisms that live in symbiotic partnerships of a fungus and an alga. Thanks to the work of retired MSU lichenologist Alan Fryday, we know that Glacier Bay has the highest diversity of lichens in the Americas.

Clockwise from upper left: Type tag; P. glaciale on substrate; Close-up of structures; View under microscope. Image credit: Matt Chansler

Digitization of MSU Herbarium collections contributes big data to big science

Specimen data from the MSU Herbarium and other natural history museums are aggregated in data portals for researchers, educators, and naturalists to use. Portals like GBIF, iDigBio, and Symbiota provide a diversity of mapping, imaging, and download tools to make these data sets useful. Researchers can ask questions about plants, their evolutionary history, and the niches they occupy using these large-scale data sets. Using specimen occurrence data that includes records from the MSU Herbarium, researchers discovered that...

All this is made possible by the deposition of specimens by botanists, decades of stewardship by herbarium members, and also to the many volunteers and students that help digitize those specimens and make them available to scientists around the world!